By: Audrey Royall, SCDNR Archaeology Intern

Five years ago, I helped the SCDNR Archaeology team process artifacts from the Pockoy Island Shell Ring Complex located on Botany Bay Plantation Heritage Preserve on Edisto Island. Shell rings were made by Indigenous peoples thousands of years ago, and are an important and unique cultural feature in the Southeastern United States. The artifacts were all recovered quickly from the shell ring complex due to the fear that the rising ocean level would soon cover them and make it impossible to ever retrieve and learn from them. After a quick excavation, these artifacts were sent to the SCDNR’s Parker Annex Archaeology Center, the headquarters of the SCDNR’s Archaeology team (also known as the Cultural Heritage Trust team). Our summer was devoted to processing a portion of the artifacts that were rapidly excavated.

I still remember the awe I felt marveling at pottery approximately 4300 years old. This internship confirmed my interest in studying archaeology and helped me to understand that archaeology is a remarkable discipline to interact with the past in our current age through the study of material culture. Artifacts provide us a way to bridge the gap that time creates between humans.

As a result of all I learned from that summer, I was excited that five years later, I would be able to travel to Pockoy Island and see where the excavation of the pottery and artifacts occurred. However, there was a caveat: one of the shell rings within the complex, Ring 1, is now completely underwater, the result of the encroaching tide on Pockoy Island. Frustratingly, the problem facing Pockoy Island five years ago is still the problem which the island is faced with today: the tide is thought to only be continuously rising further and further up the shore. The second shell ring on Pockoy Island, tucked farther back in Pockoy’s forest, has become closer to the ocean and also faces the threat that one day it too will be completely covered by water.

On our trip there in June 2024, archaeologists raced to excavate a feature—identified from a discoloration in the soil which indicates human activity in the area—since it is unknown if it will be completely underwater the next time the team visits the site. These are some of the ways that climate change interplays with archaeological work. Despite all that we know from history, there is an exponential amount of things that are unknown to us in return. To see this process happening in real time, as the shell rings are covered by the sea, is devastating to local, state, and world history. Climate change has repercussions which are felt and witnessed in real time, even at our very own shore.

Like many other people living in South Carolina, the summer months have been marked by trips to the beaches where I have enjoyed the nature that the South Carolina coast has to offer.

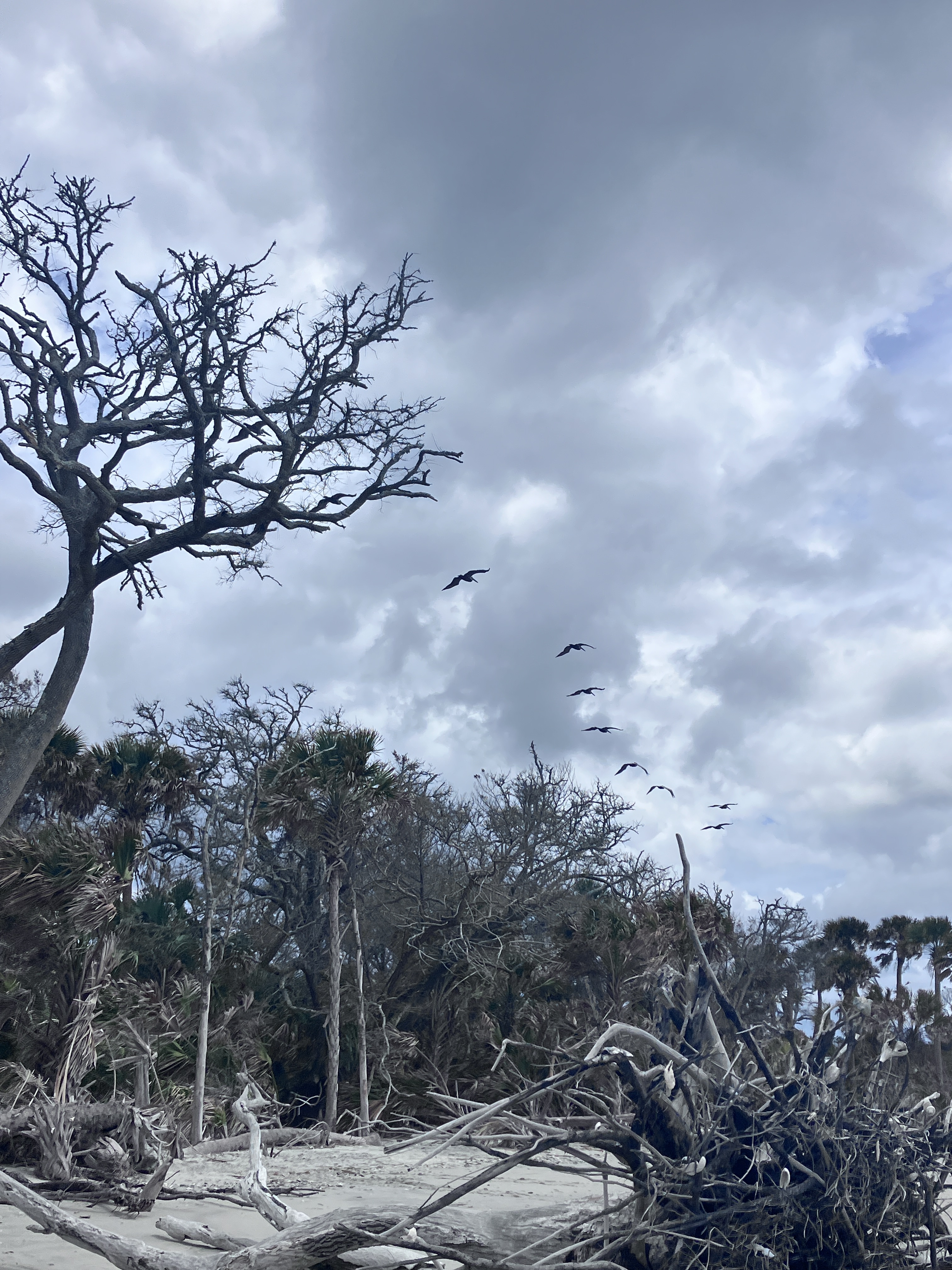

However, without awareness of the current events which are taking place, the coast’s history—both cultural and geological—is quite literally being swept away. I was interested to learn through the internship that hallmarks of the rising seawater include the presence of dead trees close to the shore, an indicator of the seawater reaching the roots of the trees and vegetation which border beaches. I had observed this phenomenon on South Carolina beaches before this summer, but never thought about its implications. Recognition of what is happening, sometimes in our very own backyards, is crucial to understand how topics such as climate change are not removed topics, but rather directly impact us in our lives.