By Spencer Smith, SCDNR Archaeology Intern

Many people who have resided in the state of South Carolina for some time, are familiar with the tropical storms and hurricanes which have assaulted the state for many years. These weather systems have the potential to not only take down trees, or flood large swaths of land, but can also damage infrastructure, and homes, trapping and displacing people. Yet these weather activities do more than just alter the local landscape or damage our infrastructure, they also impact our cultural heritage.

When a disaster strikes a local area that contains cultural heritage, tangible culture is not only affected but so is the intangible culture associated with that material. When intangible culture is threatened or harmed, it can result in a populace that has not only lost their physical culture, but also one that has seemingly lost their historical, and cultural connections to the local area. Failure to protect or save cultural materials does not only mean physical harm to resources themselves but also emotional and ethical harm to the people that have a connection to those materials. It is paramount for us at the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) to preserve and protect the cultural heritage of South Carolina and its communities, and doing so requires resources and training.

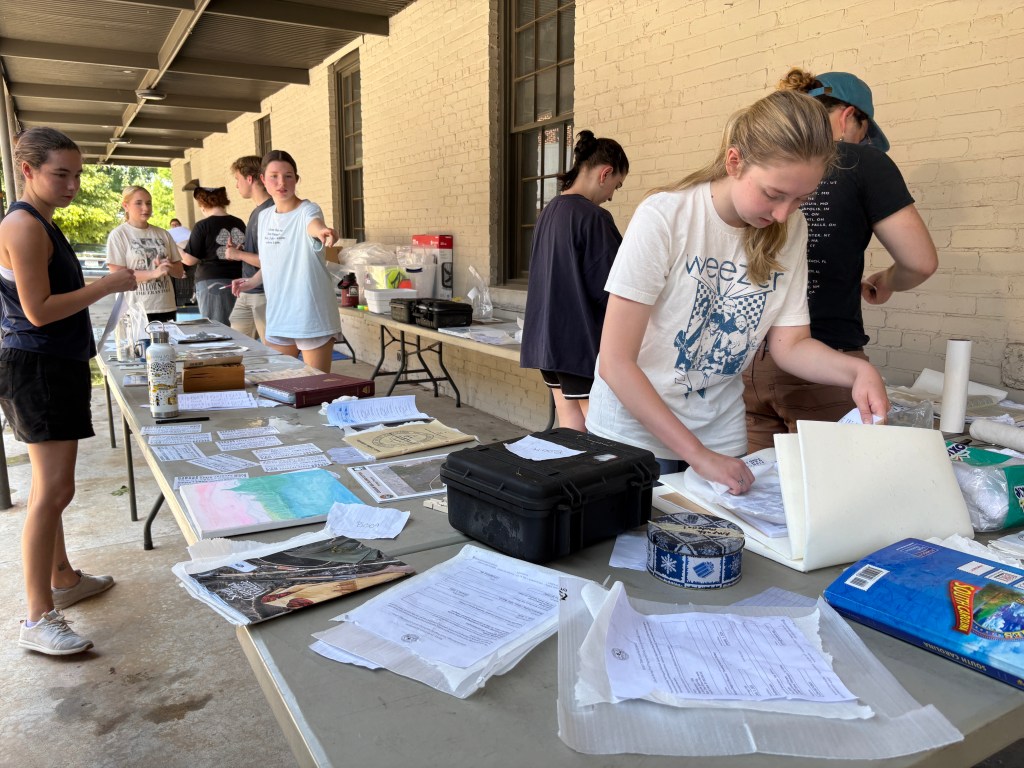

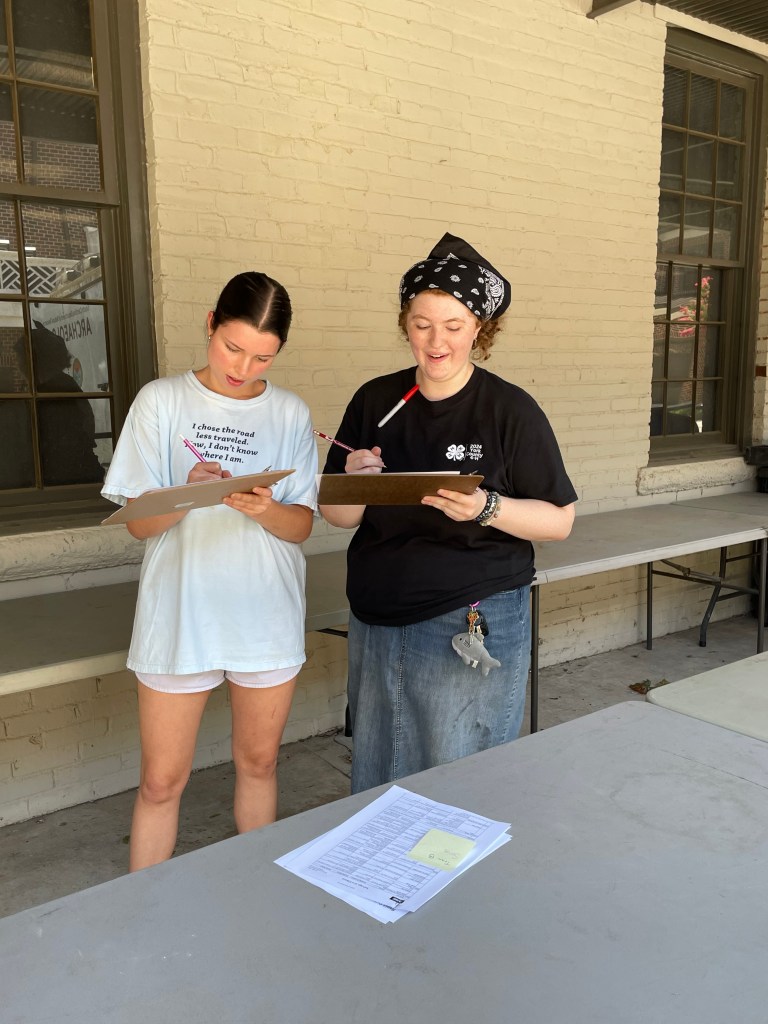

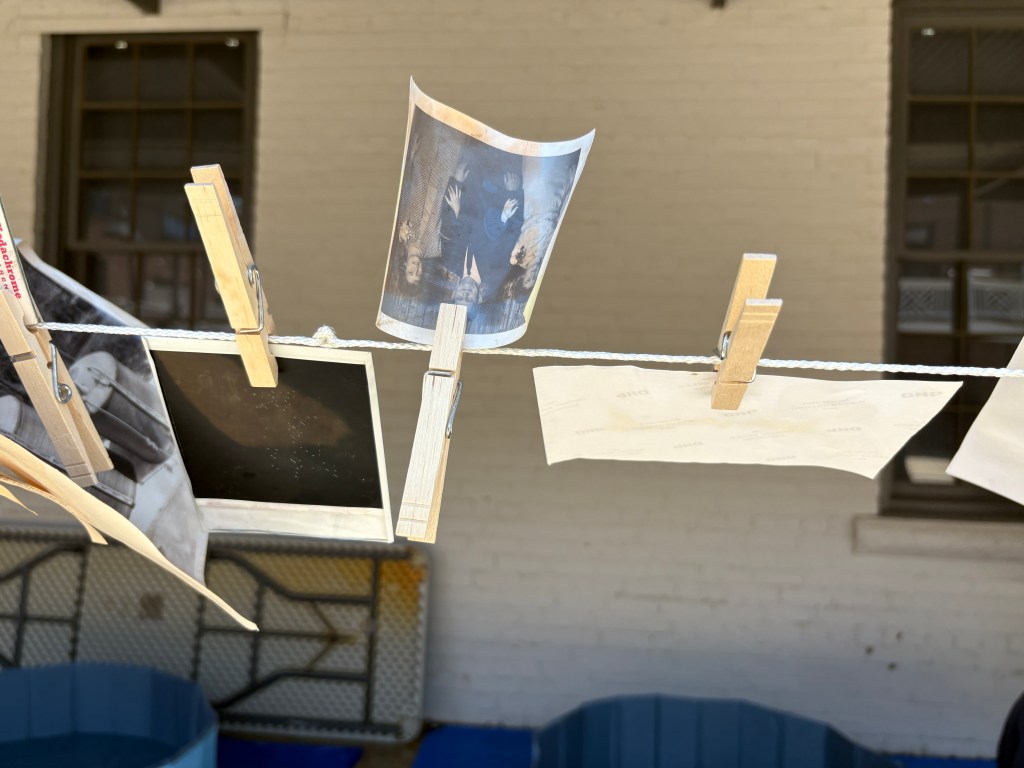

During the summer of 2025, interns took part in a simulated disaster training with SCDNR’s Cultural Heritage Trust Program (Archaeology team). During the training, interns had to develop a disaster response plan using what we learned in lectures and by using some provided disaster recovery supplies. Objects, simulating cultural resources such as artifacts, documents, and photographs were scattered about and damaged in a mock flood. In all of this, the interns had to figure out which objects to prioritize for recovery in a limited amount of time. Interns were constantly challenged during this exercise and often had to adapt original planning in order to effectively secure and preserve artifacts. By the end of the training interns had learned a lot about what did and did not work. I interviewed some of the interns and their SCDNR archaeology supervisors to see what they had to say about the training.

During my interviews with the interns, I asked how they felt about their performance during the training and what could have been better. Two of the interns I interviewed felt good about their first performance, but they noted many areas to improve upon such as being considerate of their actions, effectively communicating with one another, and knowing more on how to operate in a disaster ahead of time. I also asked the interns if there was anything that they learned from the simulation. Both interns I spoke with took away different perspectives from the exercise. One interviewee spoke on how artifacts don’t have to be damaged by a disaster, that leaking HVAC units, or busted water pipes can do just as much damage as a flood or hurricane. Another mentioned how in stressful situations like these, one has to be ready to adapt and remain calm while working with a team.

I then spoke with their SCDNR archaeology supervisors, asking them what good things the interns did during the simulation, and how the interns could improve. One supervisor of the simulation noted how they were able to remain calm with one another despite how overwhelming the simulation was at times. Another leader noted how they took their time, and fixed things along the way, and that the way they established work zones early on, helped with their workflow later. Despite this, both supervisors agreed that one thing the interns could improve upon is taking time to assess the environment, and the problem before doing work securing and triaging artifacts.

During the simulation interns found it easy to cooperate with one another and understood the importance of their disaster training. Yet at the same time, they needed to improve upon adapting their original plans and taking time to prepare for a disaster beforehand. For everyone that took part in this training, they learned valuable lessons in understanding how to prepare before, during, and after a disaster. At the same time, they gained vital insights from their supervisors. For instance, preparing isn’t the only thing that saves the day, but also having friends. One question that I posed to the supervisors of the disaster training was how community members could help out local heritage institutions. Both stated that community members can volunteer whenever they have the time to, and should be provided with opportunities to train for disaster response even before a disaster strikes. When disaster does strike people should ask if a local institution needs any help before going out to help. One supervisor stated that volunteers don’t need archaeological background to volunteer.

Museums and heritage preservation institutions are struggling with being able to manage their collections because of a lack of resources, and because of the sheer abundance of materials that these institutions have to manage. Disasters make this issue even more prevalent as it further compounds the problem. Volunteering is one way to help our local institutions, but it is not the only way. Following SCDNR and other local institutions that protect cultural heritage on social media, register for their newsletters, and attend their events. Through these small actions you can help support the SCDNR Cultural Heritage Trust Program, other local institutions that protect cultural heritage, and the community of South Carolina as a whole.

Leave a comment